Rising Interest Rates May Blow Up the Federal Budget

The different levers they can pull and dials they can turn give the Fed a whole lot of power over our financial future. When trying to stop one thing, they can cause another. Here's an example.

Article by Jeff Deist from Mises cross-posted with permission.

In fiscal year 2020, at the height of covid stimulus mania, Congress managed to spend nearly twice what the federal government raised in taxes.

Yet in 2021, with Treasury debt piled sky high and spilling over $30 trillion, Congress was able to service this gargantuan obligation with interest payments of less than $400 billion. The total interest expense of $392 billion for the year represented only about 6 percent of the roughly $6.8 trillion in federal outlays.

How is this possible? In short: very low interest rates. In fact, the average weighted rate across all outstanding Treasury debt in 2021 was well below 2 percent. As the chart below shows, even dramatically rising federal debt in recent years did not much hike Congress's debt service burden.

This is an exceedingly happy arrangement for Congress. Debt is always more popular than taxes for the same reason starting a diet tomorrow is more popular than starting today. Austerity does not sell when it comes to retail politics; spending trillions today while merely adding to what seems like a nebulous, faraway debt definitely does. And American lawmakers are uniquely fortunate in this regard. As French finance minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing infamously announced in the 1960s, the Bretton Woods monetary system created "America's exorbitant privilege." He understood how the US dollar's status as the world's reserve currency would allow America to effectively export inflation to its hapless trading partners while maintaining cheap imports at home. But he may not have fully grasped the political privilege which would accrue to Congress.

Is this privilege sustainable? That may well be the most important political question of the twenty-first century. As Nick Giambruno explains, our forty-year experiment in relentlessly lower interest rates may soon end regardless of what the Fed does. Markets and geopolitics are powerful forces. Inflation, huge projected deficits, economic sanctions on Russia, oil disruptions, and a diminished appetite around the world for propping up Uncle Sam forever all exert upward pressure on Treasury rates. The Fed proved it can and will serve as market maker and backstop for US Treasurys, with its sordid QE (quantitative easing) bond purchases after the Great Recession and its deranged response to covid. But it cannot force investors, even crony institutional investors, to buy American bond debt at rates well below inflation forever. This is not hypothetical; Giambruno notes how certain Treasury yields quietly rose five time just since the absolute lows of 2020.

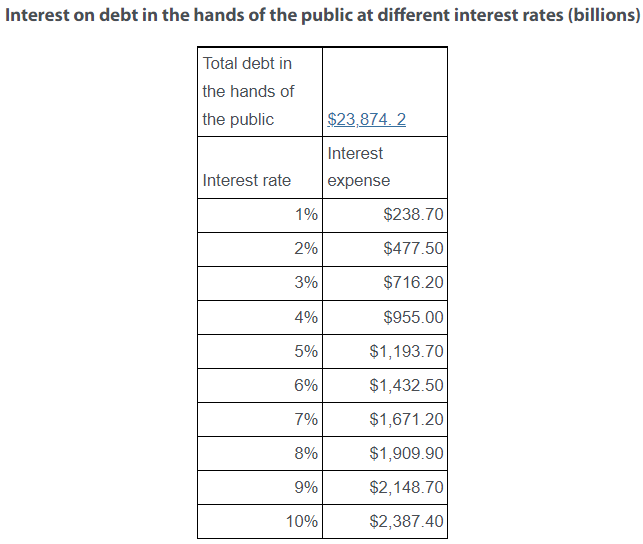

If Treasury rates continue to rise, and rise precipitously, the effects on congressional budgeting will be immediate and severe. Even if we laughably assume total federal debt remains static at around $23.8 trillion (the publicly held portion of the $30 trillion), interest rates of merely 2 or 3 percent will cause interest expense to rise considerably. Average weighted rates of only 5 percent would cost taxpayers more than $1 trillion every year. Historically, average rates of 7 percent swell that number to more than $1.5 trillion. Rates of 10 percent—hardly unthinkable, given the Paul Volcker era of the late seventies and early eighties—would cause debt service to explode to over $2.3 trillion.

Again, even 5 percent average rates would cause debt service to become the single biggest annual expenditure for Congress—ahead of Social Security ($1.2 trillion), Medicare ($826 billion), and the Department of Defense ($704 billion). The starting point for budget makers every year would be an interest expense totaling nearly half of realistic tax revenue. And keep in mind that these figures are for the existing federal debt, exclusive of the vast future deficits that are almost dead certain to happen. Seniors like entitlements, and the percentage of Americans over sixty-five is set to double by 2050. Republicans and Democrats like war, busy as they are installing more US troops in Poland and envisioning new aircraft carriers to patrol the Mediterranean (yes) and the South China Sea. What happens when the interest-bearing debt is $40 or $50 or $60 trillion?

At some point, given the sheer and utter profligacy of Congress, will the world demand junk bond rates to loan America another dime? Everyone knows the US will never pay its debts except nominally through inflation; everyone knows off–balance sheet entitlement promises cannot be kept in any meaningful way. Spendthrifts get cut off eventually, even those with powerful militaries and hegemonic currencies. This may not happen soon, if for no other reason than that the rest of the world holds trillions of US dollars too. But if American exceptionalism goes the way of the British Empire, this will be the reason why.

During the incontinent George W. Bush administration, Dick Cheney infamously chided Treasury secretary Paul O'Neill with the assertion "Reagan proved deficits don't matter." We see the same deluded thinking today among proponents of modern monetary theory, the idea that sovereign governments can command resources at will. This mentality pervades Congress, which in turn is rewarded by voters who want wars and welfare today without thought to future generations. They choose to believe the Cheneys and the MMTers, who tell them deficits and debt are essentially costless.

But debt and deficits do matter. We are about to find out how much they matter. The good news, and it is very good news, is that Americans soon may enjoy the benefits of compounding interest on savings (our grandparents can explain this to us). Civilization begins and ends with capital accumulation, the very thing politics and central banks attack with impunity. It is beyond time to reward savers and punish Congress.

About the Author

Jeff Deist is president of the Mises Institute. He previously worked as chief of staff to Congressman Ron Paul, and as an attorney for private equity clients. Contact: email; Twitter.

Image by fedrik via Flickr, CC BY 2.0. Article cross-posted from Mises.